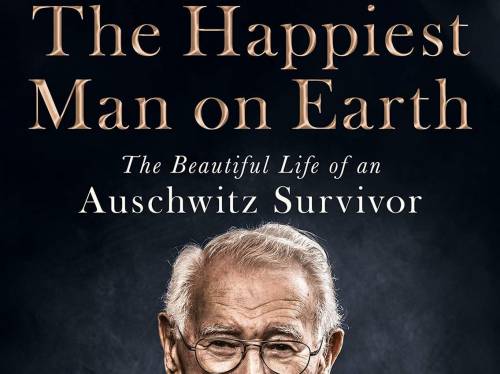

The Happiest Man on Earth

Eddie Jaku

Born in 1920, Eddie Jaku was the son of a Leipzig factory owner. “We considered ourselves Germans first, Germans second, and then Jewish”.

Hitler took power when he was 13 and Jaku was ejected from school for being Jewish. Using a false identity, he enrolled at a mechanical engineering college nine hours by train from Leipzig. He excelled.

He returned home on November 9, 1938. To surprise his parents on their 20th wedding anniversary, he returned home on November 9, 1938, The house was empty. At 5am Nazi soldiers burst in, killed his dog, beat him and sent him to Buchenwald with thousands of other Jews. It was Kristallnacht.

“We could not fathom why we had been rounded up and imprisoned. We weren’t criminals. We were good citizens,” he writes. “We were a nation that prized the rule of law above all else, a nation where people did not litter because of the inconvenience it caused to have messy streets.”

Jaku saw prisoners shot en masse and committing suicide. He was whipped and beaten. After six months, a guard with whom he had studied mechanical engineering recognised him and recommended him as a toolmaker. His father — still at liberty in those last months before war broke out — collected him from Buchenwald, but drove him straight to the Belgian border instead of the aeronautical factory to which he had been assigned.

Jaku was smuggled across, and arrested in Brussels for being German and put in a refugee camp. A year later the Germans invaded Belgium; he and other inmates walked to Dunkirk, hoping to reach Britain. They arrived during the legendary evacuation of May 1940. A colleague took a dead British soldier’s uniform and slipped on to a boat. Jaku lacked the stomach to do the same. Instead he joined hordes of refugees heading for southern France, reaching Lyons ten weeks later. Again he was arrested for having a German passport, and put in a French internment camp at Gurs, near Pau.

In early 1941 the Vichy and German governments agreed a prisoner exchange. Jaku and 800 others were put on a train to Auschwitz. He managed to escape before the train left France by loosening two floorboards.

He returned to occupied Brussels and was reunited with his parents and sister who were hiding in a boarding house attic. At night he secretly repaired machinery in a factory in return for cigarettes, which he traded for food. But in February 1944 the family were discovered and put on another train to Auschwitz. “I had some idea of the nightmare ahead of us, [but] I had no idea just how bad it would be,” he writes.

Those who did not die during the nine-day journey were greeted by a tall, handsome man in a white lab coat who singled out those few like Jaku deemed strong enough to work. Jaku later learnt that the man was Mengele, the ‘Angel of Death’. Two days later an SS officer pointed to a plume of smoke and told him: “That’s where your father went. And your mother. To the gas chambers.”

The number 172338 was tattooed on his arm. He was put in a barracks with 400 other Jews where they slept naked to prevent them escaping: ten men to a row, no blankets or mattresses, “curled up like herrings in a jar”.

Men died from the cold each night. “You would go to sleep in the arms of the man next to you just to try to survive, and wake up to find him frozen solid, his dead eyes wide and staring at you.” Others killed themselves by throwing themselves against an electrified barbed-wire fence.

Jaku survived because he was resourceful, had a friend — Kurt — who looked out for him, and was deemed an “economically indispensable Jew”. He worked as a mechanical engineer in a factory of the chemical company IG Farben, which made Zyklon B, the poison gas that killed his parents and a million others. “My education saved my life,” he says.

In January 1945, as the Soviet army neared Auschwitz, the Nazis forced its 60,000 prisoners to march towards Germany. They had no food. Some froze to death. Those who fell were shot. As many as 15,000 perished on the “death march”. “It was the hardest time of my life,” Jaku says, but he survived and was returned to Buchenwald where his toolmaking skills saved him once more.

During the war’s final months he worked in a specialist machine shop in Sonnenburg, a small camp near Buchenwald. His overseer had known Jaku’s father when they were German prisoners during the First World War. He, too, gave Jaku food.

The camp was evacuated after being bombed. Amid the chaos Jaku escaped and hid in a forest for several days. Sick and starving, “I decided I couldn’t go on,” he writes. “I said to myself, ‘If they shoot me now they will be doing me a favour.’ I crawled on my hands and knees and made it to a highway. I looked up. Coming down the road I saw a tank . . . an American tank!”

Jaku weighed barely 5st.

He returned to Brussels. He had lost his home, family and about a hundred relatives. He felt guilt at surviving when so many others had not. He considered suicide. “I had to decide what to do, to live or to find a tablet and die like my parents,” he writes. “But I had made a promise to myself and to God to try to live the best existence I could, or else my parents’ death and all the suffering would be for nothing. I chose to live.”

He married another survivor, Flore Molho, and in 1950 they emigrated to Australia, where he bought a service station and later opened an estate agency. But for three decades he never spoke about his wartime experiences.